|

In the 1930s, Pedro Linares, one of the most admired Mexican craftspersons, had a nightmare. He dreamt that brightly colored monsters appeared to him shouting: “alebrije, alebrije!” The next day, Linares sculpted the monsters of his nightmare in papier-maché and called them “alebrijes.” Very soon, alebrijes became charismatic, began to multiply, and captivated Mexicans and foreigners. Eight decades later, these monsters continue to fill Mexican minds with fantasies. Their spell has even reached Alaska, thanks to the artist Estela del Refugio Porrás Mena, better known as Macuca Cuca.

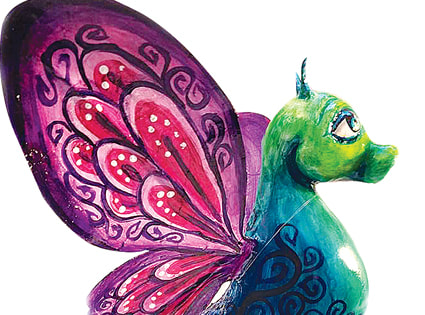

Born in the industrial city of Leon, Guanajuato, Macuca Cuca comes from a family of charros. These horsemen practice charrería, the Mexican national sport. The charros’ wardrobe has strict codes and usually includes leather pieces with decorations similar to those seen on traditional Mexican saddlery. Before moving to Alaska, Macuca Cuca worked in her family’s business, where such pieces were sold. Watching the craftspeople make them aroused her curiosity about sculptural materials and showed her the joy of creating art with her own hands. At the Universidad La Salle, in her native León, Macuca Cuca started studying graphic design, and she discovered the pleasure of modeling alebrijes with wire, tape, and paper. Macuca Cuca says that she loves building alebrijes “because you have no limits.” To sculpt them “you can mix the images of the animals you want, with the colors you want, in the most weird positions, and using the textures you want.” And so, alebrijes stretch the most fertile imagination. Once she mastered the technique for sculpting her imaginary zoo, Macuca Cuca taught alebrijes’ workshops in León, and now she hopes to start this tradition in Alaska. “First, I ask the students if they know what an alebrije is.” She then tells them that hybrid creatures, borrowing their features from both mythical and real beasts, have existed in almost every culture and throughout history. In Latin America they have been created in places as far-flung as Argentina and Mexico. In Europe, such animals can be seen in art from medieval times to the present day. In class, Macuca Cuca challenges her students to give shape to their imaginings in paper sculptures. Macuca Cuca held her first alebrijes exhibit in 2011. Two years later she won third place in a contest organized by the Arts Center of Salamanca, Guanajuato, with a giant catrina, a signature character of her work. Emblematic of the Mexican Day of the Dead, catrinas are skeletal representations of nineteenth century high-society ladies. Catrinas are inspired by an image by the engraver José Guadalupe Posada, which is a reminder that we all—rich and poor—will die. Macuca Cuca says that she likes Death as a character because Death considers all people as equals. Macuca Cuca says, “I get offended when I see very sexy catrinas. I feel it is like going back to the image of woman as an object. I also do not like it when they are shown as silly or submissive. I try to depict my catrinas with some kind of life. I often ask myself, ‘If this woman had been alive, how would she had been?’” For Macuca Cuca, sculpting catrinas is a call for women’s rights: “When you go to a cemetery and see women’s graves, you do not know if these women fought, suffered, or what they did. We can vote, we can wear pants, and wear short hair because there were women who fought for those rights, and many of them were killed.” So with her catrinas, a traditional altar also becomes a revolutionary piece. The first catrina Macuca Cuca made in Anchorage was for the 2016 Day of the Dead celebration. This 2017 she sculpted for the first time a male version of these skeletons. The catrín, whom she affectionately calls Don Melquiades, was inspired by early twentieth century gentlemen. |